The Brightness of Light

Renée Fleming still thrills

Bookended by two works by Richard Strauss (Dreaming by the Fireside — Symphonic Interlude No. 2, from the opera Intermezzo and Also sprach Zarathrustra), Kevin Puts’ The Brightness of Light was the main attraction for Thursday and Saturday’s National Symphony Orchestra concerts, thanks to the presence of Renée Fleming. Brightness expands on an earlier work, 2016’s Letter from Georgia, a set of orchestral songs with a libretto by Puts based on letters of Georgia O’Keefe. That project, their first collaboration (their connection is the Eastman School of Music), prompted Fleming to suggest Puts expand Letters to include Alfred Stieglitz, O’Keefe’s older, philandering husband. Two years later we now have Brightness, a dialogue between O’Keefe and Stieglitz told through their letters (again, the libretto is by Puts based on their letters), which, along with photographs of O’Keefe and Stieglitz together and apart, and photographs of O’Keefe’s art, are projected above the orchestra during the roughly forty-five minute work.

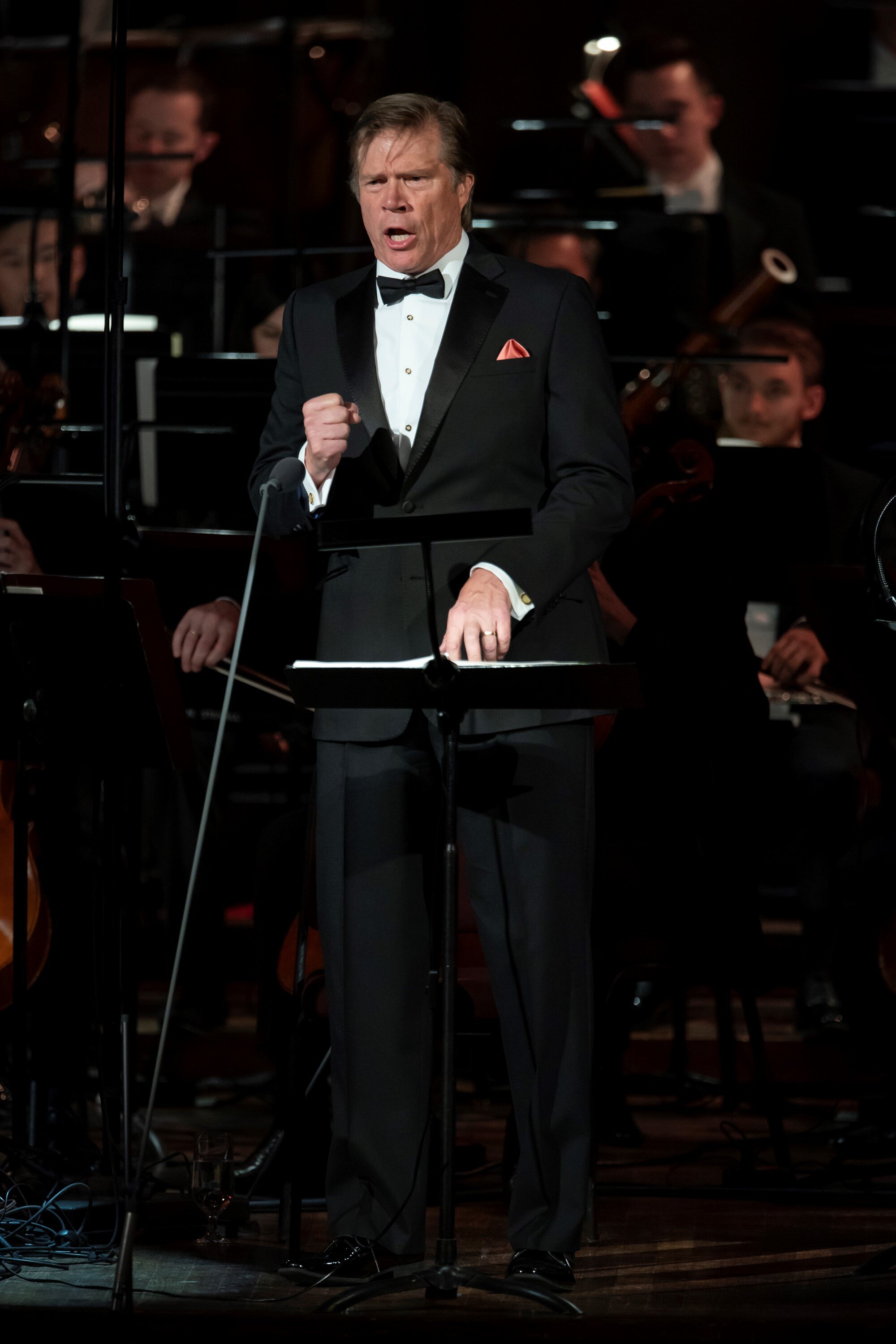

It’s a satisfying piece, similar to Jake Heggie and Gene Scheer’s Camille Claudel: Into the Fire in its ability to bring its subject(s) to life. But like Heggie and Scheer’s work, which had the great fortune of Joyce DiDonato’s participation, I can’t help wondering how much of the positive impression Brightness creates is a reflection of Fleming’s star power. It’s a great vehicle for her, but Rod Gilfry, who sings the Stieglitz parts, doesn’t leave nearly the same impression, nor is he really given much of an opportunity to do so, given that his early expressions of awe and desire soon give way to laments and respect offered from a distance. There are also unintended, jarring juxtapositions created whenever photographs of O’Keefe are projected while the spotlight shines on the glamorous Fleming standing beneath, singing her prose.

Still, recent years have seen the 47-year old Puts create one operatic success after another (Silent Night, Elizabeth Cree, The Manchurian Candidate), and he succeeds here in giving a very large orchestra much of interest to say about these two people. I suspect Brightness can (and should) succeed with other singers, and might possibly be more affecting without Fleming’s overwhelming (but always welcome) presence.

There are twelve sections, two of which are well-constructed instrumentals. The correspondence Puts used to craft the libretto spans from 1915, when they met while she was still an unknown artist and he was still married to another woman, through Steiglitz’s death in 1946. Two final arias are a “fantasy” detailing O’Keefe’s feelings of longing after his death, both for Stieglitz and perhaps for what could have been between them, or perhaps what could have been between her and someone other than him. They’re the most compelling parts of the work, at least in Fleming’s hands. At first their voices alternate, and Puts’ orchestral pallette expands as O’Keefe’s artistic vision grows and then blooms into something greater once she moves to Taos, New Mexico.

The early sections feature recurring appearances of rapid-fire 32nd notes from a marimba (or xylaphone?), as if to highlight the passage of time or distance, like ellipses pushing the protagonists and their history forward. Sad waltzes, nods to Bach, and heartbeats drawn by strings, winds, and brass pop through, and at critical moments Puts has the orchestra create crescendos of emotion. A faltering, scratchy violin mimics O’Keefe’s own efforts with the instrument. Through all of this Noseda’s habit of waving his arms in massive circles is replaced by a more circumspect beat-keeping. The movement called “The High Priestess of the Desert” was, at least in this initial encounter, the most musically arresting moment as Puts creates an aural transformation of O’Keefe’s artistry portraying her to evolution into a visionary American artist, accompanied by photos portraying her aging face.

The final sections, “Friends, and “Sunset,” illustrate O’Keefe’s loneliness and the ravages of time on her heart with sharp clarity, starting slowly and tentatively until the percussion builds to a strike of lightning. Fleming’s vibrato at this point serves as a reminder that while her tone may have darkened in recent years, her ability to thrill an audience with her voice remains undiminished. By the way, young sopranos looking for audition pieces would be well served to consider both of these arias.

As for those Strauss pieces, it’s hard to find a reason for their presence other than that The Brightness of Light requires an unusually large orchestra so why take advantage and program some equally big pieces? As was the case with the Wagner concert the week before, the brass and horn sections were problematic, while the strings sounded marvelous, providing a lush tone that’s becoming the orchestra’s calling card under Noseda.

Pictured above, L to R: Rod Gilfry, Gianandrea Noseda, Renée Fleming. All photos by Scott Suchman.