The beat goes on

In April of 2016 I had the good fortune to interview Esa-Pekka Salonen. During the conversation we talked about a Mahler’s Ninth he conducted with London’s Philharmonia Orchestra in Berkeley. I told him it left me speechless, and on the verge of tears. He replied “…of course Mahler goes to a similar kind of place — it’s an “end of life” kind of thing, and as none of us knows what it really means, a nonverbal vision of it is most likely better and more accurate than something that you try to describe in words.”

So while it’s tempting to set the performance of last Saturday night’s Mahler’s Ninth by the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra framed against its current woes, it’s also, in my mind, inappropriate: it was not programmed in response to current events, but scheduled over a year ago as the penultimate subscription series of the season.

Still, one couldn’t really escape the poignancy of an orchestra many feel is about to fall into the abyss performing one the repertoire’s most monumental and wrenching “farewell”s in light of recent news. It was evident from the moment one walked into the hall and saw just a handful of musicians onstage tuning up beforehand: that is if one got there early enough, before they too vacated the stage, leaving it looking empty and somewhat forlorn.

This was by design, with the musicians opting to enter as a unit in a gesture of solidarity, begun after the BSO’s executive leadership announced the cancellation of its summer season and cutbacks to the orchestra’s pay and benefits achieved by reducing the length of the season from 52 weeks to 40, and paid vacation time from 9 weeks to 4, effective immediately, announced just hours before a performance, and just weeks after the release of their summer season’s details, including a new music festival. The choreography received a standing ovation from segments of the audience.

Oy.

Questions abound. First and foremost, why on earth did BSO’s leadership give the okay to plan for a summer season, and allow those plans to be announced, if the organization’s finances were so tenuous the whole thing had to be scrapped just weeks later? Any way the leadership of the BSO spins those decisions, they look inept and foolish. On the other hand, those same leaders have been pretty transparent about sending the message that 40 weeks is on the way since at least November, so why are the musicians acting like they had no idea any of this was about to be dropped on their heads?

Since then it’s been the usual rounds of invective and insinuations that have characterized similar recent disputes in American orchestras. The issues are largely the same, the arguments familiar, and the responses somewhat predictable. The major differences boil down to those defined by regional demographics and endowment size, which define the available options for both sides, which will in turn define the outcome. We’ll find out more on June 16th, but in the meantime I wouldn’t put any money on a quick resolution.

And what about the music?

Conducted by Marin Alsop, the orchestra gave the performance everything they had, and the results were impressive. It was an especially good evening from the brass and wind sections, both of which seemed to feed off the energy in the room and returned it with a clarity and focus I sometimes miss in these groups. Was Alsop striving for an elegiac tone, attempting to wring out all of the Tristan-like elements she could to create sense of pathos and grandeur? It sounded that way to me, and toward the end of the first movement she and the orchestra achieved a glorious fin de siècle weariness.

The second movement was appropriately coarse and lively, but the shift in tone away from the first movement’s emotional core proved hard to recapture later on. The longer the orchestra waltzed on, the more obscure their destination became. Hence, whether they were waltzing over a cliff or pushing on to the horizon remained emotionally vague. The thread to the first movement had been cut.

The third movement fared better, the percussion driving the horns and brass toward a gravitas just beyond reach, but full of exuberant energy and punch. Alsop kept the tempo fast, but not fast enough to render it frivolous.

For me, few symphonies strive for a fourth movement apotheosis as much as this one, seeking that cathartic climax when, as Salonen put it, “none of us knows what it really means, a nonverbal vision of it is most likely better and more accurate than something that you try to describe in words,” but it is still incredibly moving to experience. It wasn’t present for me in this performance, but I did notice it was there for others, including a few members of the orchestra who wiped tears from their eyes when it was all over.

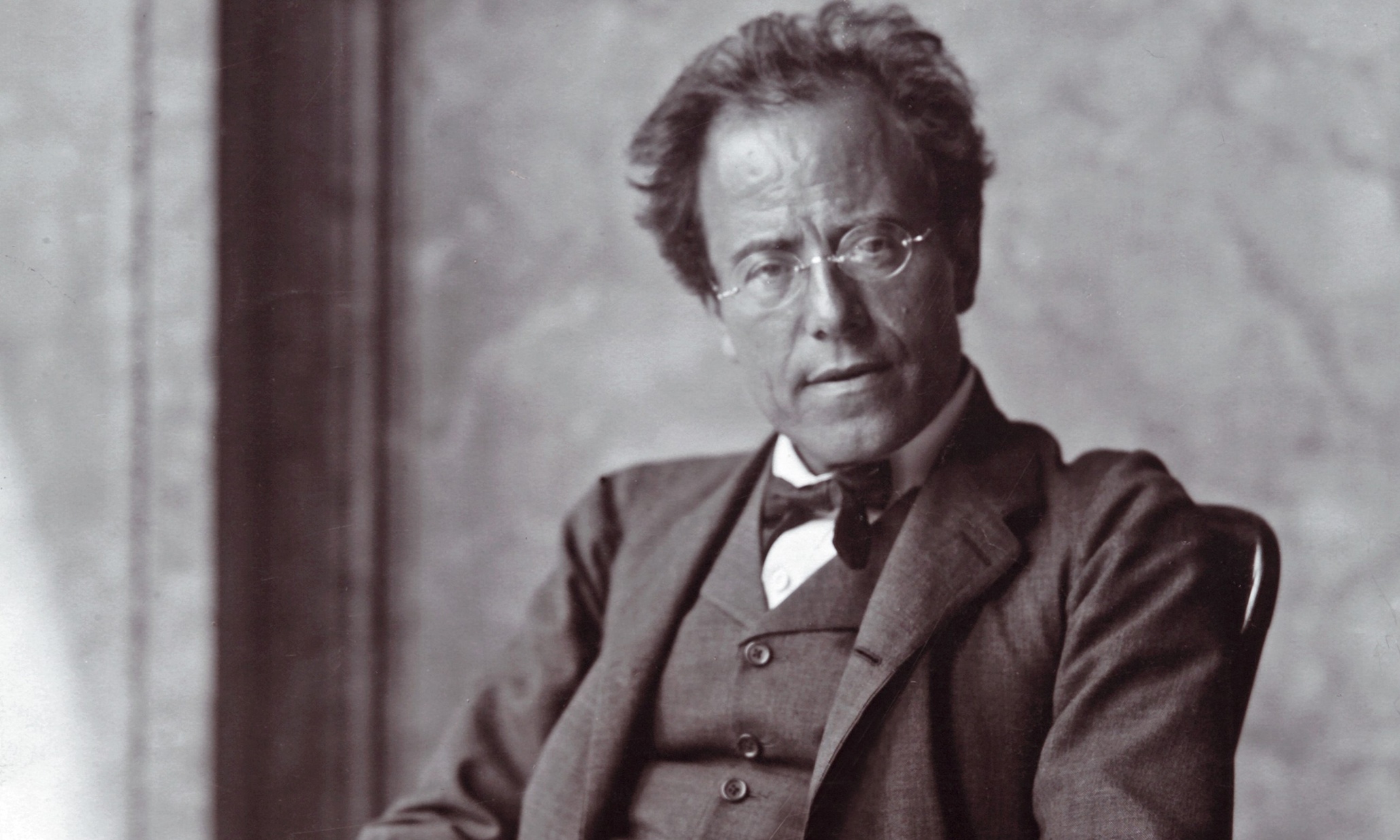

Photo above by Angus Clyne.