Champion

Defining the boundaries between opera and musical theater isn't all that interesting to me, mostly for historical reasons: in the days before vaudeville, Broadway, and pop culture as we know it today, opera essentially was musical theater, as well as popular culture. I'm also not against the burgeoning trend of American opera companies presenting American musicals in opera houses, at least as long as we're talking about classic musicals like Porgy and Bess or Oklahoma! (though I'd feel differently about seeing The Phantom of the Opera, Godspell, or Into the Woods get the same treatment, and chalk that up to my own prejudices and taste). And until last week, as I was watching Washington National Opera's engrossing and well-crafted production of Terence Blanchard's Champion, I have never sat in an opera house and wondered whether a work presented as an opera wouldn't be better served by being labeled and presented as musical theater.

Champion is billed as "an opera in jazz" -- it's scored for an orchestra plus a four-piece jazz quartet comprised of piano, bass, drums, and guitar, and delivers its most effective musical moments in jazz idioms. The libretto by Michael Cristofer is based on the biography of Emil Griffith, the bisexual pro boxer from the U.S. Virgin Islands who became the world welterweight champion. At the weigh-in to his second rematch with Benny Paret in 1962, Paret insulted Griffith by patting him on his ass and calling him maricón, Spanish slang for "faggot." In the final round of that fight Griffith pummeled Paret so badly the fighter collapsed into a coma at the end and died a few days later. Personally and professionally, Griffith was never the same after Paret's death and his career went into decline. He died suffering from chronic boxer's encephalopathy in 2013 at the age of 75. If that story isn't fertile ground for operatic treatment I don't know what is.

I saw Opera Parallèle's production of Champion just over a year ago at the SFJazz Center in San Francisco, which I didn't like at all. The SFJazz Center doesn't have a traditional proscenium stage, and while that's not a prerequisite for successfully presenting opera, in this case it made for a production that was a tiring and confusing mess, exacerbated by poor blending of the jazz quartet and the orchestra as complimentary forces. At nearly three hours, it felt like an endurance test, and I walked away from it thinking it was a worthy experiment gone awry. Because of that experience I approached WNO's production with some trepidation, curious about how it would play in a real opera house with a full orchestra, but not really expecting it to change my opinion that Champion was a loser. I was wrong.

Adapting the original production from Opera Theatre of Saint Louis, WNO's Champion is good and occasionally great opera. Champion also raises some interesting questions about contemporary opera and audience expectations, at least in major houses, especially since it comes on the heels of WNO's production of Dead Man Walking, another contemporary opera that struggled to fill the house even though it music and structure adhere more closely to traditional opera.

First, who is the target audience for a new opera composed by a jazz musician about a black, bisexual athlete? On one hand the answer to that question presents a tantalizing opportunity to bring in new audiences -- for a whole lot of people, that must sound like a much more interesting night out than a going to an opera by Handel. On the other hand, how do you sell that to the significant portion of the existing audience that supports large opera companies who won't even turn out for Wozzeck or Lulu, much less Dead Man Walking? That's a big challenge, and while the house looked packed on opening night (and many have noted the audience was one of most diverse they've ever seen at WNO), subsequent performances had (and have) a lot of unsold tickets.

Which leads me back to the question of should Champion be viewed and/or marketed as an opera or a work of musical theater?

On their website Dallas Opera states the difference between operas and musicals is that "in a typical musical dialogue is spoken by the characters who occasionally burst into song. In most operas, the singing never stops. Even instructions as mundane as, “Open the door,” are sung rather than spoken." Anthony Tommasini of the New York Times has offered a more precise definition, "Both genres seek to combine words and music in dynamic, felicitous and, to invoke that all-purpose term, artistic ways. But in opera, music is the driving force; in musical theater, words come first." Writing in The Guardian in 2002, Andrew Clements broke it down further in a piece acknowledging the trickiness of the task:

The simplest and most concise distinction I can come up with is that in an opera the drama is largely generated by the music, while in a musical it is largely defined by the text, with the music taking an illustrative and expressive supporting role. I'm sure there are exceptions to both definitions (Bernstein's Candide and Sondheim's Pacific Overtures, perhaps), as well as works that seem to be crossbreeds (such as Kurt Weill's Street Scene), but that is as precise as one - well, this one - can get. The narrative function of motifs in Wagner's Ring, or the dramatic significance of key sequences in the finales of Mozart's Da Ponte operas are the kinds of devices that musicals abjure; their narrative threads are sustained through the words, whether in the dialogue or in the separate musical numbers.

By these definitions, none of which I would disagree with despite believing they are somewhat incomplete, Champion is an opera. Where it gets a little sticky is that its most driving music comes from the jazz quartet, not the orchestra. That shouldn't prevent it from being presented as opera, but it does raise the issue of whether or not it's suitable for the mission of traditional, large opera houses.

And on that score I'm a bit stuck, thinking Champion might have better success being presented as a musical that's actually an opera, which might relieve it of the elitist stain that sadly still clings to the form, and perhaps opera's sky-high production costs and ticket prices, all of which might lead it to be seen by a wider audience than large opera companies can attract in today's competitive climate. One downside to presenting it as a musical is that doing so would necessitate nightly shows in place of opera's staggered performances, which give opera singers' voices a needed rest between performances. Double casting is one solution (albeit an expensive one), amplification is another (albeit an unpalatable one for opera fans). On the other hand, WNO's production is so well realized that it's something few if any theater companies could pull off without the financial resources equivalent to a Broadway production, which makes it an even riskier bet and thus an unlikely contender to have ever been staged in the first place given Broadway's (mostly) conservative and risk-averse tastes. And it's precisely the resources WNO has dedicated to this production that makes its Champion such a winner.

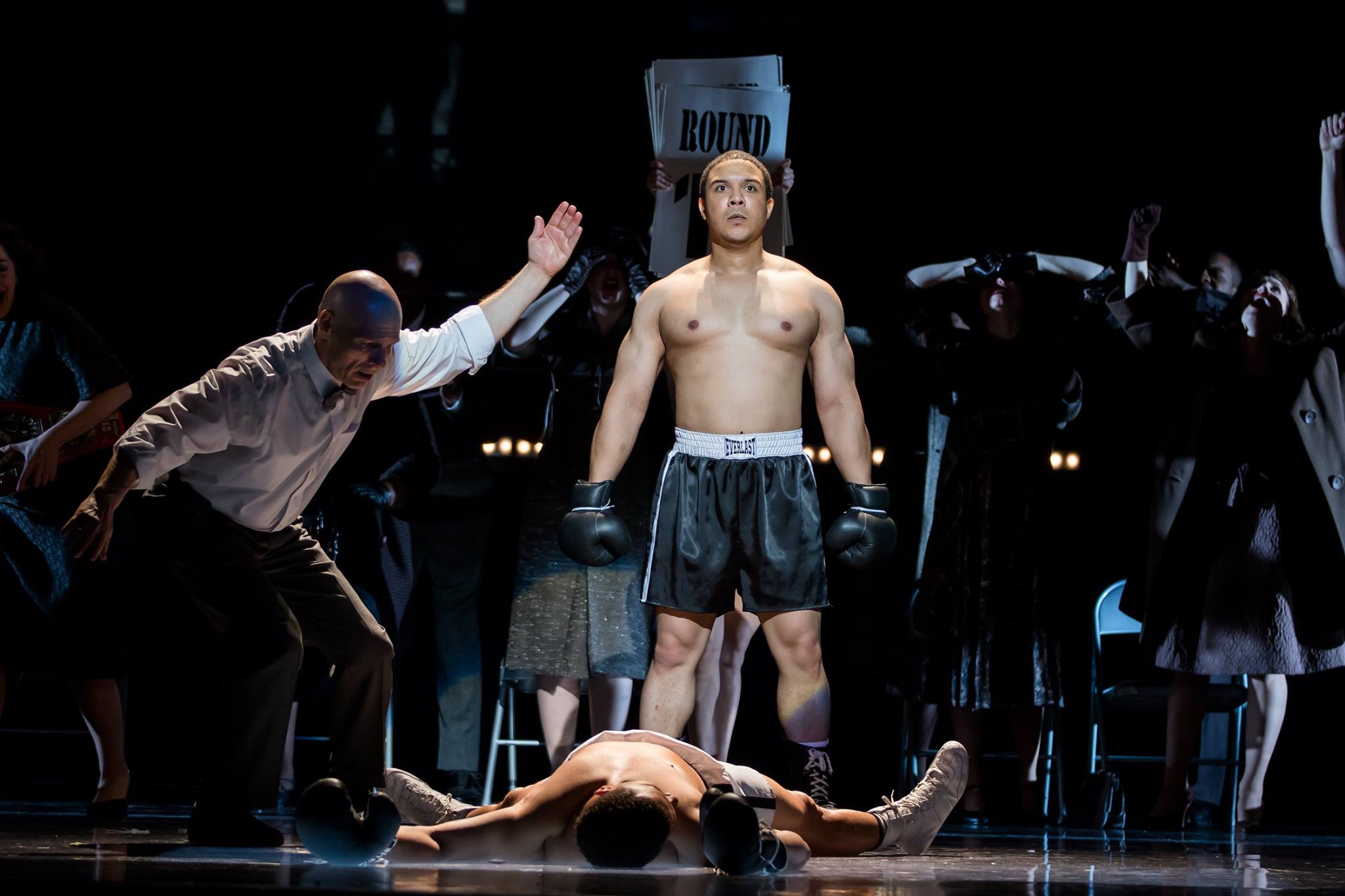

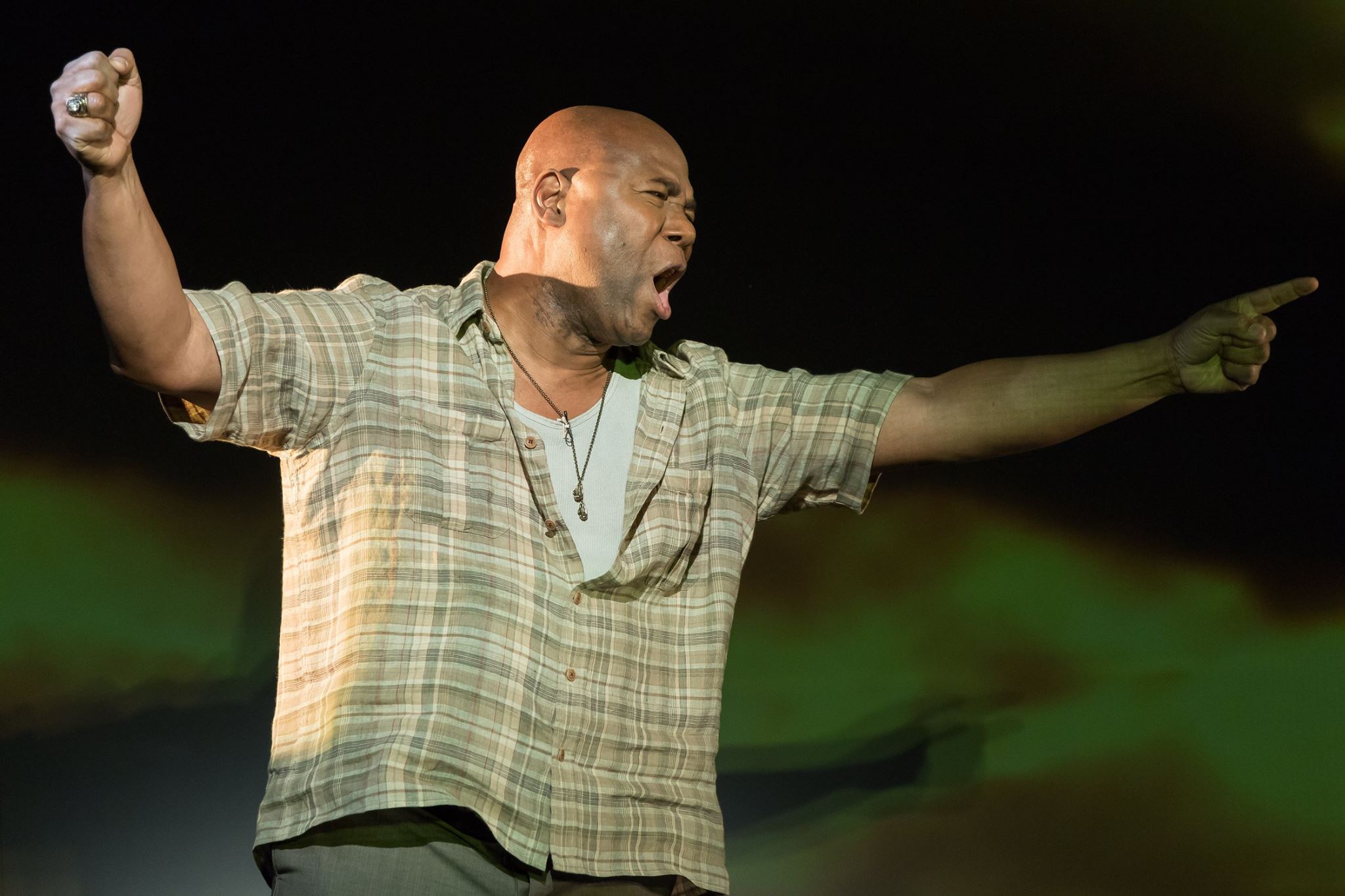

Opening with a scene in a boxing gym displaying the more refined and precise physicality required of boxers, Champion then introduces an aged, suffering Griffith (bass Arthur Woodley, who also sang the role in San Francisco) wondering about a lost shoe. From there the story goes through Griffith's life alternating between flashbacks and the present, some staged as big production numbers, others as intimate moments (as Griffith's mother, Denyce Graves' strong performance is more dramatically moving than impressively sung). In the first act these lively scenes unfold one after the other, supported by Greg Emetaz's marvelous projection work and WNO's chorus and dancers, creating the impression that while Griffith (bass-baritone Aubrey Allicock) had the physical attributes to be a boxer, he had a pliable, open-hearted nature that made him an unlikely contender, that in the end boxing was the means to an end that lay far outside the violence of the ring. The act builds a narrative arc concluding with the fight which results in Paret's death.

The second act is the long aftermath of that night. Too long, in fact -- Champion could lose a half hour of it and be better off for it -- but the scenes depicting the young Griffith's post-Paret path from riches to ravagement, which include being the victim of a brutal assault and seeking forgiveness from Paret's son (Victor Ryan Robertson plays both Parets), interspersed with the older Griffith's conversations with his adopted son Luis (Frederick Ballentine), repeatedly nail their emotional mark under James Robinson's direction. Cristofer's libretto delves into a number of themes dealing with race, sexual identity, masculinity, family, and forgiveness, yet manages to keep them allat ease with each other within the opera's frame. That's no small feat, and his success on that score gives Champion a strong dramatic punch even if Blanchard's orchestral and vocal writing are more serviceable than memorable.

However, the sections of Blanchard's score written in jazz and the opera's big dramatic moments deliver, and combined with the solid cast, able conducting of George Manahan, and the committed resources of WNO, this production of Champion should be appreciated by a number of diverse audiences. As an opera, it has its challenges, but I can't imagine it getting better treatment than it has with this production.

Champion runs through March 18, 2017. Get tickets here.

If you liked this, like A Beast in a Jungle on Facebook for more.

All photos by Scott Suchman.