SHIFT

SHIFT: A Festival of American Orchestras makes its inaugural debut in the nation's capital.

SHIFT, a weeklong music festival celebrating American orchestras, made its inaugural debut last week in the nation's capital. Rising from the ashes of the now-defunct Spring for Music festival that ran for four seasons at New York's Carnegie Hall, SHIFT marks the first collaboration between the Kennedy Center and Washington Performing Arts, the capital's two powerhouse arts presenters. While Spring for Music focused on innovative musical programming, SHIFT is interested in showcasing what orchestras do in their communities as well as in concert halls. The invited orchestras (Boulder Philharmonic, North Carolina Symphony, Atlanta Symphony Orchestra & Chorus, and The Knights) performed full-length evening concerts at the Kennedy Center's Concert Hall and also led musical nature walks, performed at the Smithsonian, appeared in schools (and bars), pop-up concerts, participated in symposiums, gave workshops, and otherwise delved deep into the D.C. music scene for a few days.

Those activities outside of the concert hall are fun, illuminating, and worthwhile for drawing attention to the numerous things orchestras do to enhance and contribute to their local communities, but in the end, for most of us, it's what happens inside the hall that really counts. And since what's happening in concert halls is undergoing extraordinary pressures to adapt to myriad social and economic changes, the timing for launching the SHIFT festival couldn't be better, as both a showcase for American orchestras, and as a forum that examines ways to reposition their place on a shifting American cultural landscape. I missed most of this year's events but managed to attend the concerts on Friday and Saturday night at the Kennedy Center by the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra & Chorus and The Knights. However unintentional, taken together the two concerts felt like a primer on everything orchestras are doing wrong and right to attract and engage audiences.

On Friday the ASO performed Christopher Theofanidis' Creation/Creator, a massive fifteen-part oratorio presented as a "theater of a concert," complete with video projections, a second stage amidst the musicians for the vocal soloists, a few props, some amplification, and a phalanx of chorus members. Done well, these kinds of extravagant spectacles can add real meaning and depth to a work, especially contemporary pieces. This was the case when I attended the San Francisco Symphony premiere of John Adams' El Niño in 2001, a performance I found so emotionally moving I gave away every cent I had in my pockets to homeless people I encountered on my home after the show. But spectacle can also detract from the music, or create outsized expectations for the sum total of a performance, and in this case all the added hullabaloo exposed the lack of creative spirit in Theofanidis' piece, despite strong performances from everyone involved, especially the chorus and a formidable line-up of soloists including Sasha Cooke, Jessica Rivera, Thomas Cooley, Nmon Ford, and Evan Boyer, all ably led by conductor Robert Spano, who was instrumental in ASO's commission of the work (which they've also recorded).

Theofanidis has skills, if not art, evident in his ability to conjure an aural painting of twinkly lights made from spiraling musical notes that prompts a delightful vision of Van Gogh's The Starry Night in one's mind while his music accompanies a sung quote from the painter. However, any early hopes that the composer is working toward developing an impressionistic musical narrative on the creative spirit or a meditation on a/the creator's power is soon disappointed as each new section becomes increasingly ham-fisted or misguided in delivering its message: look -- here's a quote from Rumi! Here's something from the Rig veda! You know this is important and profound, meaningful stuff! Rather than surrounding the listener/viewer in the aural equivalent of a Van Gogh painting, experiencing Creation/Creator is like being trapped inside a Thomas Kinkade painting for 90 grim minutes.

At times the music stops altogether for a scriptural passage, or in one egregiously misjudged section, for the bizarre sudden entrance of an actress portraying Margaret Cavendish dressed in 19th century clothes (a wardrobe choice that's off by two centuries, but who cares) to read something that's supposed to be funny (it wasn't). A screen above the orchestra projecting Theofanidas' libretto (culled from many sources) inadvertently kept driving the thinness of his ideas home as it displayed quotes from Keates, Schubert, Bach, Berlioz, and numerous others like a set of Oblique Strategies for Dummies. Instead of creating a sympathetic link from the works of these creative masters to Creation/Creator, the quotes only underscored that it's better to experience creativity than have it explained to you. As the piece dragged on it was hard not recall concert experiences where listening to the music of Bach, Berlioz, Beethoven, Wagner, Mahler, Messiaen and others produced a sense of awe through nothing more than the music's creative energy and performance. Nothing along those lines was to be found here.

Would Creation/Creator feel so oppressively pretentious without the theatrics and bombastic presentation? It's possible -- there's an appealing Britten-esque quality to some of the music and Theofanidas is deft at crafting melodic passages. It's also possible that among the majority of the audience who enjoyed the concert there were a few newcomers to classical music drawn to the Kennedy Center out of curiosity and inexpensive ticket prices who really enjoyed the whiz-bang aspects of performance and will come back for more, and let's hope they one day find their way to a performance of El Niño.

Or better still, that they came back the next night and caught the superb concert put on by The Knights and the San Francisco Girls Chorus, who played to a half-full house and without any multimedia extras, yet proved beyond a doubt that the only thing musicians really need to wow an audience is a well-chosen program and a stage full of talent to make it soar.

The Knights are a collective of classical musicians from Brooklyn led by Colin and Eric Jacobsen, two engaging brothers who serve as its Artistic Directors. It's a younger group than most orchestras, and an attractive one, made up of a rotating roster committed to making the concert experience relevant and accessible. They manage to successfully walk the line between maintaining a reverence for the classical tradition and treating it casually in a way that frees the music from the tradition's sometimes suffocating confines. Watching them onstage, The Knights look like they're having a genuinely good time playing serious music, and playing it well.

Their concert began with composer/vocalist Lisa Bielawa's My Outstretched Hand (commissioned by The Knights in 2016), which uses excerpts from the 1902 autobiography of Mary MacLane, a 19 year-old woman who lived in Montana. Bielawa, who is also the Artistic Director of the San Francisco Girls Chorus and a former member of the Philip Glass Ensemble, has a masterful grasp of polyphony. The piece works like a tapestry of voices flowing with and then against the instruments to create a sense of emotional confusion alternating with youthful certainty. Not all of the lyrics were easy to make out (no surtitles were used), but the voices of the young women of the Girls Chorus built a kaleidoscopic portrait from MacLane's excerpts that was spellbinding in its sense of mystery yet projected a sense of youthful awe and wariness of the world around her.

The Girls Chorus participated in most of the remaining program, with some members featured as soloists in Vivaldi's Gloria in D major. Conductor Eric Jacobsen pointed out this Gloria was originally composed for a girls orphanage, and thus the audience was hearing a rarity in that this performance would sound the way Vivaldi intended it to be heard. The 300 years separating Bielawa's piece from Vivaldi's didn't seem so much to be a contrast in genres or styles as it did a continuation of something fundamental found within a young woman's sense of yearning. Brahms' Psalm 13, "Herr, wie lange," written in 1859, continued in this vein.

After the intermission, during which a number of the chorus members were found having excited conversations in the lobby with friends, family, and well-wishers, came Aaron Jay Kernis' Remembering the Sea (Souvenir de la Mer), a three part meditation of the horrors of recent terrorist acts and the ideologies behind them, featuring a text by the poet Kai Hoffman Krull. In the program notes Kernis writes "the first [movement is] a dialogue between a young girl and her departed mother -- memories of closeness and touch..." The second movement is a Dies Irae and the third is a conversation taking place in English and French. Musically Kernis' work is quite different from the music of the concert's first half in its asymmetry and sharp angles, but its thematic link couldn't be clearer, and its seriousness forged a chain linking it with the rest of the pieces that gave the concert, and the presence of the SF Girls Chorus, an underlying sense of purpose in using music and the concert setting to present a historical and emotional perspective of how life has (and has not) changed, especially the lives of young women. The subtext was there if one wanted to look for it, and if one didn't there was still wonderful music marvelously performed, a joy of its own needing no other justification.

But here is where I want to point out that even if one failed to pay any attention to what was going on beneath the surface of The Knights' program, I believe it would be impossible not to feel its presence during the performance. It was a weight that could be felt without experiencing a sense of heaviness, nor was it the kind of self-conscious presence that derailed the ASO's concert the night before. It was just intelligent programming, and cannily deployed so that it succeeded on numerous levels as nourishment for both the ears and soul. And it was enjoyable, especially the final number, The Knights' own ...the ground beneath our feet, a ciaccona based on a Baroque-era bass line by Tarqunino Merula that turned into a romp before violinist Christina Courtin stood up and brought it home with one of her own songs to the delight of everyone present -- on the stage and in the seats.

Comparing the two concerts, perhaps unfairly, perhaps unnecessarily, one could draw the conclusion that expanding the concert experience to include all the razzle-dazzle modern technology allows might draw a larger crowd, but The Knights delivered a significantly more rewarding experience with no other gimmicks than excellent musicianship and a sense of purpose.

Next year SHIFT features the Fort Worth Symphony Orchestra, Albany Symphony, Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra, and National Symphony Orchestra, taking place at the Kennedy Center and other locations around D.C. from April 9 – 15, 2018. The press release notes "Collectively, the participating orchestras will spotlight repertoire that has been influenced and inspired by literature, history, geography, varied cultures, and nature and will encompass collaborations with vocalists and choirs, dancers, star solo instrumentalists, and six living composers." Put in on your calendar.

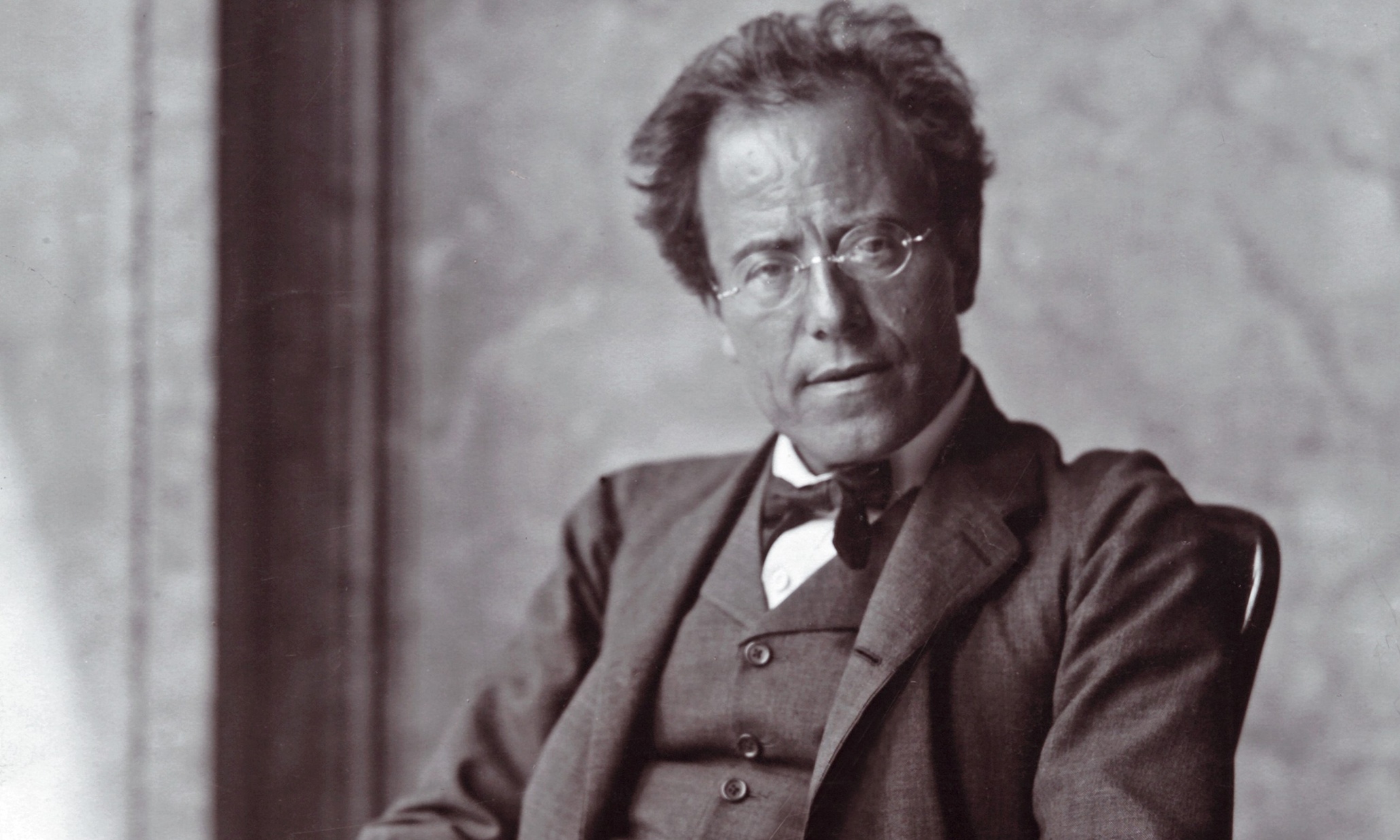

Pictured: The Knights